Fashion’s Full Circle

- Jan 20

- 6 min read

From formidable footwear of the 16th century to Gucci’s modern gowns, the Cleveland Museum of Art’s new exhibition traces how certain themes in art and fashion perpetuate throughout time.

Written by Nicole Wloszek-Therens

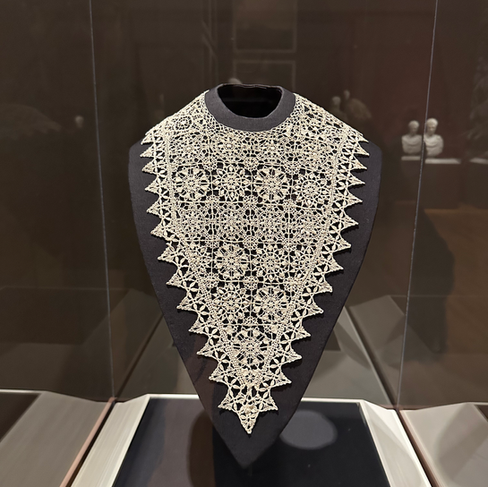

My platform boots clicked on the smooth marble floor beneath me as I made my way into the Cleveland Museum of Art’s new exhibition, “From Renaissance to Runway: The Enduring Italian Houses.” Wall to wall, the room was full of mannequins dressed in ensembles inspired by shining armour, cloaks encrusted with celestial symbolism and elaborate gowns – both delicate and powerful at the same time. My eyes bounced from texture to textile, landing on the footwear inside a glass case right in the middle of the room.

Each shoe had some similarities to the boots I was wearing. A platform a few inches thick, a chunky heel, a bit of personality. I looked down at the informational tag on the side of the display. 1930s. Huh.

My favorite pair sitting inside the clear box were a rainbow sandal, with a lofty platform made up of layers of color stacked on top of each other.

They almost looked like they could be displayed in the window of a shoe store today, a pair that I would certainly stop and stare at. I wondered – did anyone ever actually wear them? I thought about if someone had run around town in these, who would she be? I pictured a woman with short hair curled close to her neck. She wore a silk scarf that always matched her shoes and probably lived in Rome or Milan, with an especially chic career like acting or modeling.

I felt a sort of connection to this made-up woman in my mind. Maybe, despite the near-100 years between our timelines, we weren’t so different. After all – we liked the same kinds of shoes.

The Cleveland Museum of Art’s new exhibition “From Renaissance to Runway: The Enduring Italian Houses” demonstrates that fashion is a circle rather than a straight line. Many modern patterns, styles and structures are hundreds of years in the making – inspired by garments of fashion’s past and artworks that continue to shape design today.

“Fashion is always going to pull references from one period into another,” Darnell-Jamal Lisby, associate curator of fashion at CMA, said. “Back when the Italian creative community was attempting to devise their identity in the shadow of Paris fashion during the turn of the modern 20th century, they looked to the Italian early modern period, and its artistic legacy, as the vehicle to subvert.”

It’s the largest fashion exhibition that has been displayed at CMA, with more than 100 modern and contemporary Italian pieces on view. They are displayed alongside Italian textile, decorative and fine arts from the 1400s to the 1600s, and allows visitors to see firsthand how the past and present collide through historic artwork, whether it’s displayed on a wall and or modeled on a mannequin.

Designs from houses like Armani, Bvlgari, Ferragamo, Gucci and Valentino are displayed beside artworks from the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods, coming from CMA’s own collection. Presented side-by-side despite the centuries between them, the exhibition illustrates the historical period’s influence on contemporary Italian designers.

The modern style of platform shoes that I am familiar with had a revival in the early-to-mid 90s with designers like Vivienne Westwood pushing the boundaries of footwear on the runway. At Westwood’s Anglomania fall/winter 1993 fashion show, model Naiomi Campbell walked (and stumbled) in 12-inch platform heels. The absurdly tall, crocodile skin shoes were inspired by Westwood’s deep love for 18th century art and fashion, encapsulating the extravagant and sometimes impractical nature of high fashion of the time. While some think these emerging styles were a throwback to trends started by groovy girls and guys in the 1970s, they were actually inspired by earlier trends, starting with the “original” platform – the chopine.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History, the chopine was developed as early as the 16th century. It was a shoe with an exaggerated platform, reaching as high as 20 inches. The style was particularly popular with Venetian women of status, and it was believed that the higher the shoe, the higher the level of nobility.

Lisby wrote in the article “Welcome to the Renaissance” that Salvatore Ferragamo’s designs like the rainbow platform sandal on display in CMA’s exhibit were inspired by analyses of these high-platform chopines, which were “worn in the early modern period by women who could afford the fashion.” This is a statement that highlights just how often the cycle of high-fashion repeats itself – in more ways than one.

Style itself is cyclical in nature from one century’s fashion to the next, continuously drawing inspiration from the past in both designs and themes. A perpetuating theme that tugged at my mind when looking from an oil painting of a woman in luxurious fabrics hundreds of years ago, to the gowns from Gucci and Versace encrusted with stones that cost more than my college education, is that fashion was, and still is, a symbol of nobility for the elite.

Acknowledging this doesn’t undermine the culture, craftsmanship and history that I was surrounded by. However, I realized that from the chopines of the 16th century, to red-bottom Louboutin’s of today, high fashion has always been a calling card – a way for the upper class to identify and impress.

“The social status translates today with certain brands,” said Amy Bradford, who previously owned a line of footwear boutiques called Amy’s Shoes on the west side of Cleveland. “If you have a red bottom, people know that’s an expensive shoe.”

A thread that links Baroque art, Renaissance styles and today’s high-fashion pieces is their shared role in reinforcing elite identity. According to “Baroque and Rococo Fashion” by Umer Hameed, an educator in textile and fashion design education, the Baroque period itself was a representation of an era of luxury, evolving under royal courts and social hierarchies. The fashion was structured and stiff, while being dramatically adorned, reflecting the splendor of monarchs like Louis XIV of France. Wide skirts, stiff dresses and lace collars were just a few pieces that became symbols of nobility.

By the turn of the century, fashion began to shift. As the middle class grew, styles became more playful, natural and practical. As highlighted by Hammed, extreme fashion excesses from towering hairstyles, extravagant accessories and exaggerated silhouettes came to symbolize the looming decline of the aristocratic elite just before the French Revolution.

Excess defined the style of the Baroque period, but also elevated fashion into a display, something to be seen and considered. This exhibit prompts the viewer to see style and design in the same light as traditional art, with clothing of today’s designers displayed next to traditional Baroque-era artworks and old Italian textiles.

“There’s the thought process and the design, but instead of being on a wall or being a sculpture or something, it’s on a human, it’s on a body,” Bradford said. “It’s either equal or beyond, because it’s wearable in some form or fashion.”

Lisby, who holds a bachelor’s degree in Art History and Museum Professions and a master’s in fashion and textile studies with a focus on history, theory and museum practice, said that fashion and traditional art can be appreciated in the same way. Otherwise he wouldn’t have a career that is based on the intersection of fashion and art.

“I wouldn’t be a fashion curator if that wasn’t the case,” Lisby, the museum’s first fashion curator, said. “Or even the fact that there is a growing number of fashion exhibitions in major global art institutions.”

Lisby worked in the fashion industry for the last decade in both private and public sectors. He has experience in museum education, exhibition commissions and curation, leading to his move to Cleveland in 2021 for the position. “From Renaissance to Runway” is the third exhibit that he has curated since he started at CMA.

He hopes that visitors don’t just leave with an appreciation for the garments on display, but also with awe inspired by the intersection of fashion and art, and a gained understanding into its historical context.

“From emotional lenses, I just hope that people take away a sense of joy and wonder,” Lisby said. “From an educational perspective, my hope is that audiences can approach the dichotomies of fashion as vehicles of understanding the past and present, and as a process that contextualizes respective creative and sociocultural zeitgeists.”

From platform shoes designed nearly a century ago to intricate beading patterns woven into dresses today, styles worn hundreds of years ago are still reflected through modern trends. The exhibit “From Renaissance to Runway” demonstrates that no matter how much time passes, one thing remains the same: from social influence to similarities in design, fashion is a circle.

The first-of-its-kind exhibit will remain on view through February 1, 2026 in the Kelvin and Eleanor Smith Foundation Exhibition Hall.

Tickets can be purchased ahead of time at www.clevelandart.org.

More fashion photos by Nicole Wloszek.